Even though it seems we are now seeing a vanguard of South Asian talent. Many forget the pioneers who established themselves throughout the footballing ecosystem despite the limitations society imposed upon them.

Yet many believe South Asians to still be invisible in the game due to their alleged historic disinterest in the sport. A belief further compounded by stereotypical associations of South Asians opting to engage with other sports like cricket and hockey. An ideology still deeply ingrained in the footballing pyramid.

Lost in this veil of prejudice and widely accepted truths lie the forgotten stories of those who dared to defy. The tales of South Asian trailblazers who made names for themselves in the sport they were told was not theirs. One particular name is still remembered in one of the greatest footballing cities in the world.

Glasgow, a city steeped in sporting history and the home of one of football’s greatest rivalries. The Old Firm. It was in this city that Mohammed Salim, a boy born in Calcutta would become the first of his community to represent a European club.

South Asian involvement in football is not an alien concept. Many are unaware football’s earliest origins remain bedded in Asia. Early century China played suju or kickball, arguably the sport we now love in its rawest form.

Football itself would be brought to the subcontinent in the 1850’s by the British Empire well before its codification and before the establishment of the Football Association. However, it did not arrive as an innocent pastime but would serve a greater purpose.

For the colonisers, sport was not just a game. It was a tool, it was propaganda and it was powerful. In this way sport could be used to subjugate, control and influence natives.

At first this was the case, by introducing these new sports then gatekeeping its access and rules meant the British would be held as the custodians of these games.

Over time this dynamic began to shift and instead natives saw this British invention as the perfect forum to express with a ball the feelings of resistance, freedom and patriotism that had been suppressed for so long.

It was in this powder keg that Mohammed Salim was born in 1904. Raised in a typical household at the time, those around Salim assumed he’d follow the simple life path.

However in 1911, Salim was exposed to one of South Asian sports biggest triumphs. When a barefoot Mohan Bagun faced the British East Yorkshire Regiment in the final of the IFA Shield. They would win 2-1, crippling the image that Empire had created.

Never before had the might of the West been made to seem so fragile. Outdone at their own sport by their ‘primitive’ counterparts playing the gentleman’s game in the most atypical way.

Witnessing this victory set alight a burning passion for a sport Salim would one day make his own. After finding his feet in the Indian game, Salim joined Mohammedan Sporting Club in 1934. He would figurehead an era of dominance for the side in the Calcutta League Cup, leading them to five league titles in a row.

His sporting successes did not go unnoticed and Salim was invited to represent an India XI that would face off against China’s Olympic team in two matches. This would become the first time an international football fixture was hosted on the subcontinent.

The first match ended in a draw, with the second match set up as a winner takes all but…

Salim had gone missing.

Police and government officials searched frantically for the forward. Questioning and quizzing all possible persons involved, putting adverts in local papers with many fearing the worst for their star player.

Instead Salim was on a steam-liner via Cairo headed to Britain. Influenced by compatriot Mohammed Hasheem who himself worked on steamships. Having heard of and seen Salim’s footballing prowess he encouraged him to try his hand further afield. A journey that would eventually take him to Glasgow, Scotland.

When he arrived in Scotland, Hasheem managed to get word to Celtic coach Willie Maley. Telling him that ‘India’s greatest player had arrived on Scottish soil.’ Maley was eventually convinced, deciding to put on a specially organised trial at Celtic Park. Salim was surrounded by professionals in the home of a football club that had been thriving since 1887. Unproven and untested at the top, the man from Calcutta had no doubt he could match up to the best.

Despite the prejudices and attitudes present within this era. It was in fact not the colour of his skin that raised the most eyebrows. Instead it was Salim’s commitment to playing barefoot against opponents proudly sporting their Scottish steel-toed boots and studs.

Salim had to receive special dispensation from the sporting committee to allow him to complete his trial and later take the field in matches. Early observers noted he was…

“No doubt a man of fine natural gifts and therefore was a spectacle to behold.”

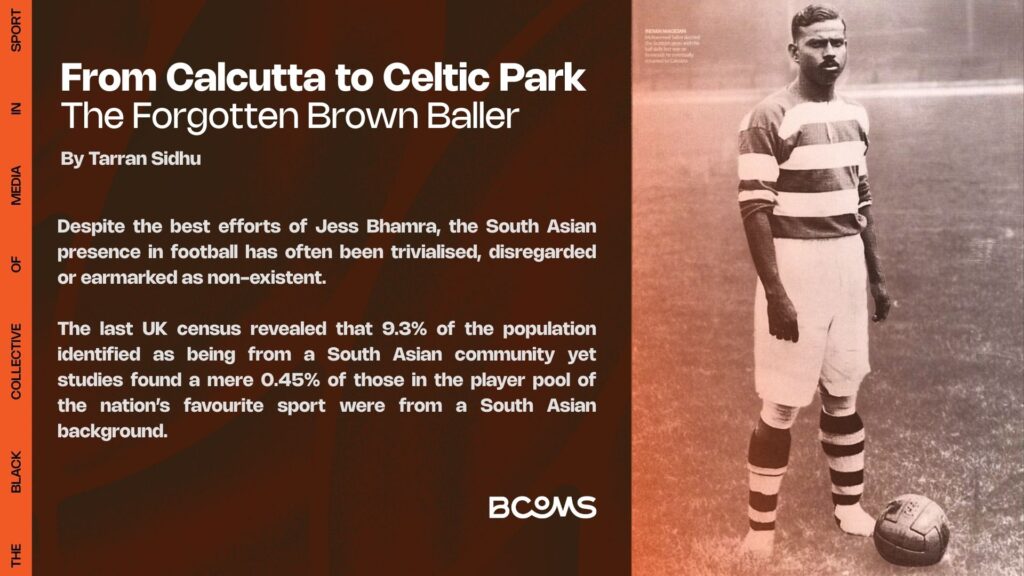

Following his trial, Celtic aimed to test the Indian starlet’s talent in a designed reserve game. Salim pulled on the famous green and white shirt and ran out to face Galston in August 1936.

The fixture amassed a crowd of over 7000, fascinated by this mystic figure playing football in Europe in a way many could only describe as alien.

Celtic would triumph 7-1. Salim would claim MOTM and the newspapers would hail him the…

The Indian Juggler!

“A magician when the ball was at his bare feet”.”

Salim’s adventures did not stop there, with newspaper interest piqued as well as the team’s fanbase. Salim was scheduled to play a second fixture against Hamilton a few weeks later on. 5000 turned up this time to see him make the headlines again, scoring a penalty in the match and further impressing with the ball at his feet.

This fixture would serve a greater purpose than just sporting acclaim. Despite papers at the time still loading their headlines and pieces with racial epithets or connotations. The images published would tell a different story and remain of great significance even today.

One image shows Celtic trainer Jimmy McMenemy wrapping the feet of Salim, readying him to play. At a time where those who looked like Salim were inferior to those who surrounded him. When the white presence could not be overshadowed by any darker counterpart.

Here was a white man touching the feet of a brown man. Performing an act of service and support without a care for his colour, caste or social standing.

The photo held greater weight back home. Where the act of touching one’s feet is revered with great respect and importance in Asian culture. For the time, to see this in popular media would have been unfathomable.

Regardless, at Parkhead the message was clear. The only colour that mattered was the club’s strip and all those that bore those were to be considered an equal part of the team.

Salim played his final fixture on September 14th in a 3-2 win over Partick Thistle. His performances left Celtic and the fans convinced, ready to offer Salim the opportunity to play his football in Glasgow for the season. For many this would have been their greatest dream and the height of sporting success in the era.

However, for the boy from Calcutta who had become the man in Glasgow. His dream was to return to his land, his people and his home.

Celtic tried desperately to convince him to stay. A contract offer of nearly £1800 was laid on the table, Salim refused. A charity match where he would earn 5% of the gate receipts, Salim again declined and instead suggested the money be given to local orphans. Even offers from Germany and beyond came for the Indian starlet but Salim’s mind was made up.

Five days after his final fixture, Salim would set sail for India on the same ship that brought him to the city where he became a silent sensation. Back to India, he took the famous green and white shirt, his shorts and a gold watch as tokens from his European escapade.

Upon his return home, his exploits and adventures were not celebrated or praised; instead he would continue to play football for Mohammedan as he had done before, winning additional titles for the club.

With the current state of play for South Asians, many wonder how the game could have progressed had Salim stayed to play his football in Europe.

What it would have meant to see a brown face playing amongst other colours, playing with or without boots during the Empire years. Proving that those from another land were not totally different.

Had the temptations of a mother’s cooking not lured India’s star home, would the sport have found a place of esteem in a nation of over a billion? Would the stereotypes have been allowed to flourish and hinder?

If Britain had opened its doors to those it had conquered sooner, bringing forward the Eurasian culture movement earlier. Would Mohammed Salim have stayed in Glasgow had his people been around him? Could Glasgow’s dish of pride Tikka Masala be enough to convince him to stay?

It may seem comical in parts but Salim couldn’t do it on his own. Had the call of his people been to excel and build a life on foreign soil like they would all follow decades later. Then could he of sacrificed the allures of returning home?

For the questions to which we don’t have answers, there is one thing we do know. Towards the end of Salim’s life, he became ill. His son saw this as an opportunity to remind the world what his father had accomplished. He wrote to Celtic, asking for help with his father’s treatment. He received a letter back, alongside £100 to help with Salim’s care.

That cheque was never cashed because the real reward was that Mohammed Salim still lived in the European memory, he still had a home at Celtic FC and he had the ultimate right to proudly be declared as the first Indian footballer to play in Europe. His time may have been brief but the impact especially on those that hear the story today is profound.

To know someone who looked like me, came from the same land as me and lived out the same dream as billions of young boys and girls across the world in that era is enough fuel to propel our South Asian footballing movement on. Knowing it had claimed its space before at the summit of sport, here’s to one day knowing it will find its way back again.